Architectural Styles

To first-time visitors, Cabbagetown's streetscape of well-maintained Victorian housing, an eclectic variety of styles and an intimate scale gives the sense of a small, well-kept town from the nineteenth century. Some streets, such as Metcalfe, present a view that is very close to that of a century ago. But this neighbourhood is not a museum. Behind many restored facades are some starkly modern interiors and rear constructions. Down the lanes can be found the cutting edge of industrial conversion. Out of sight and above the rooflines, Cabbagetown's upper stories include some stunning and creative deck gardens. With the community's mix of income, some hidden renovations are directed by hired designers and architects; others are thoughtfully planned and carried out through the payment of sweat equity.

The historical experience of Cabbagetown is expressed through its streetscape: the building facades, gardens, fences and other elements that are visible from the sidewalk. This area, unique in the density of original buildings and the general quality of restoration, presents a rare view of the nineteenth century for us to-day. Homeowners contribute to that when they make changes consistent with the style of their homes.

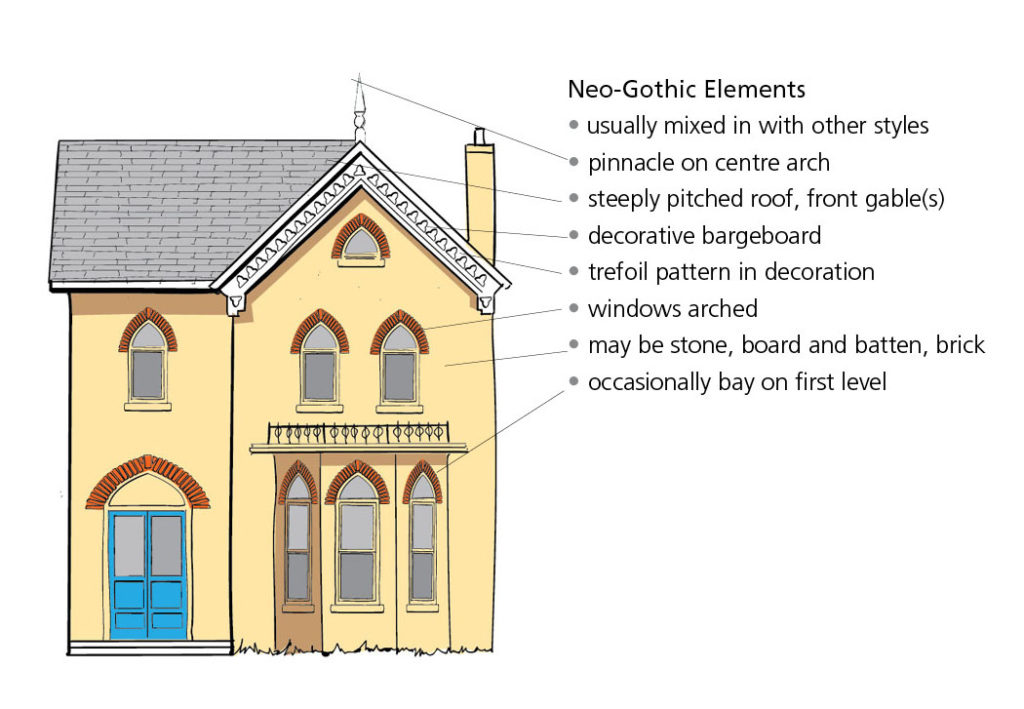

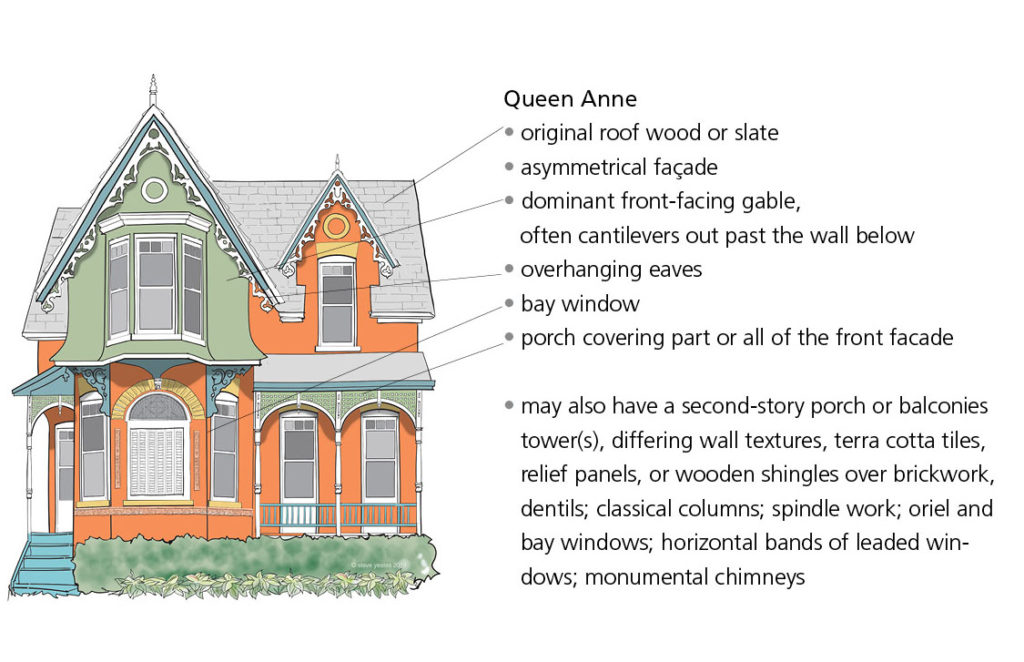

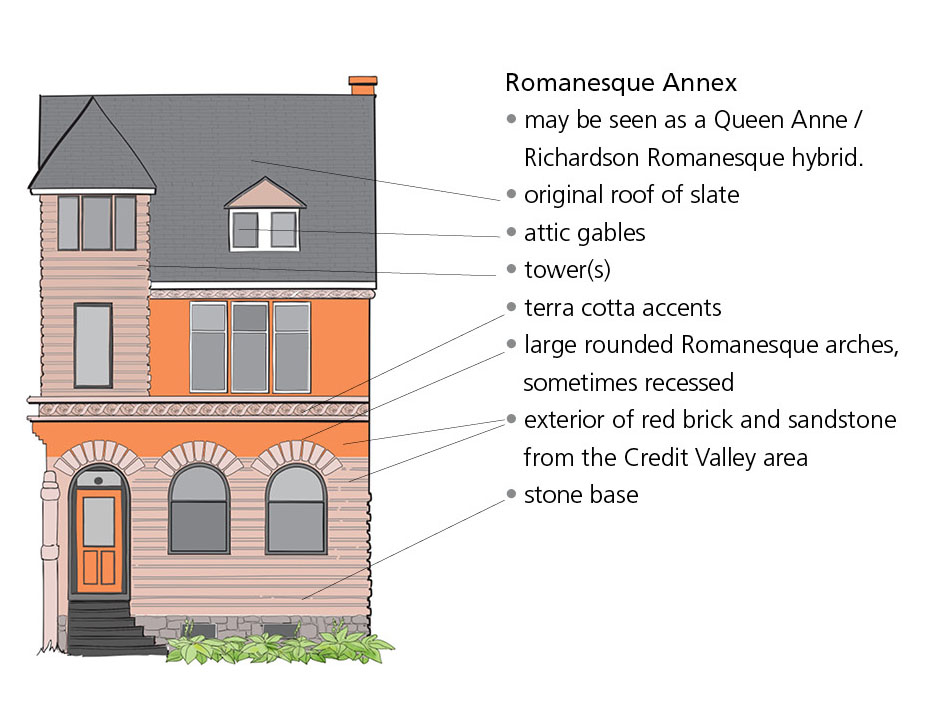

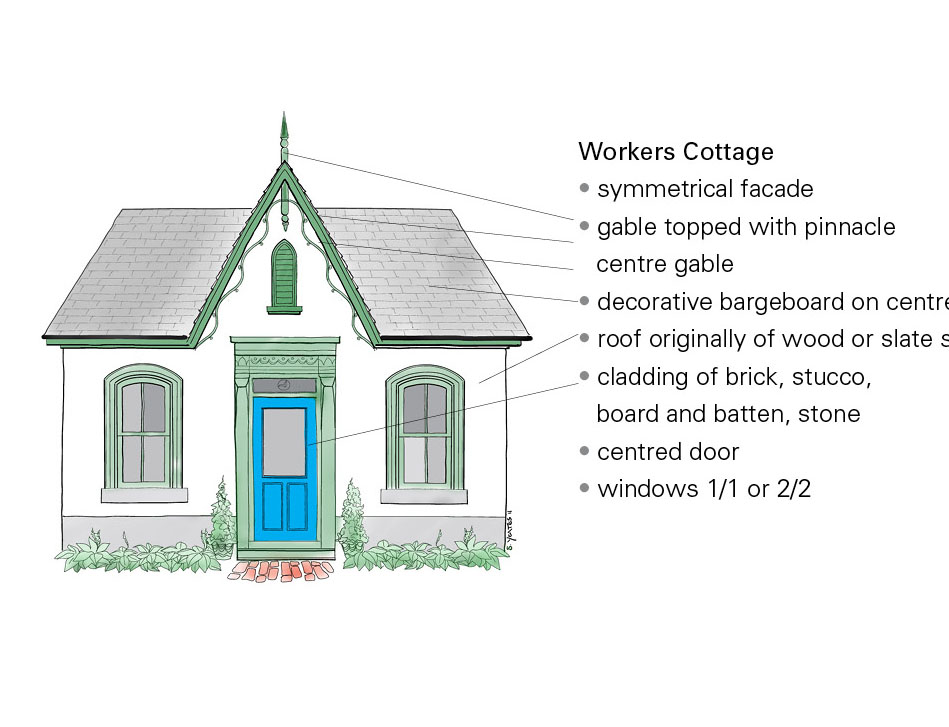

What style is your home? We often identify our homes as Victorian, but "Victorian" isn't a style, it's a period. Like us, the Victorians loved to play "architectural dress-up" using designs from other times. In the decades following the Victorian era new styles appeared with their own characteristics.

Knowing Cabbagetown's styles gives some guidance in making decisions when a home or its details are being restored. Identify your home's style below from the drawings created by CPA Board member and designer Steve Yeates.

PROPERTY SEARCH

The CPA developed in partnership with our sister organization, the Cabbagetown Heritage Conservation District Committee, a compendium of properties where you can find information about your own Cabbagetown home. Using the Address search field or drop down options, search for a property within Cabbagetown to learn some historical facts.

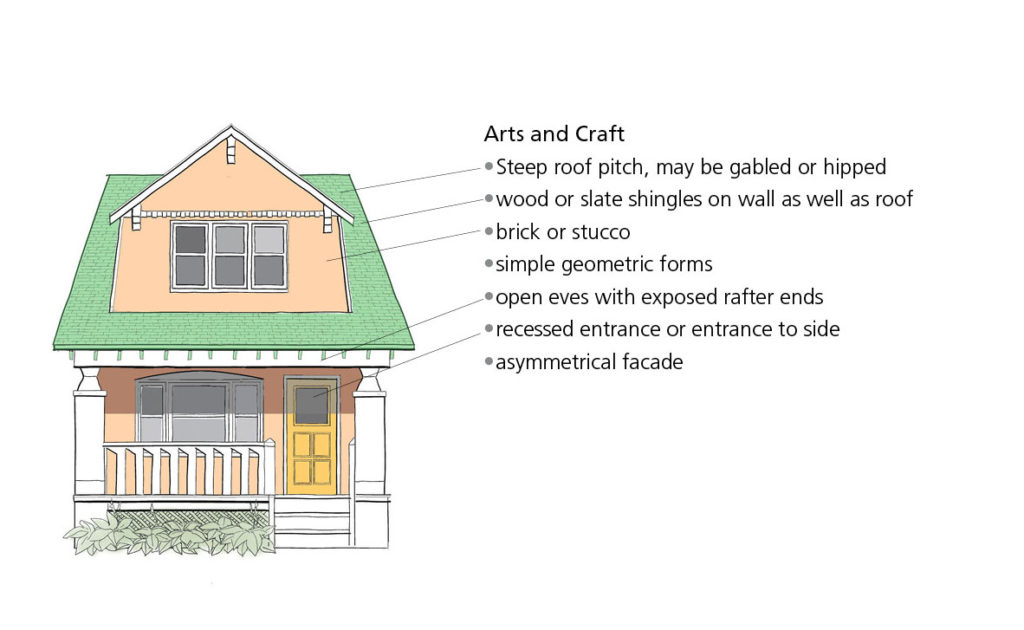

Inspired by the “honesty” of Medieval building, and theorized by Ruskin and William Morris in the late nineteenth century, the Arts and Crafts Movement advocated traditional materials and building practices, good craftsmanship and simple ornamentation.

In Toronto, the leading Arts and Crafts exponent was the architect Eden Smith. His design for what is now the Spruce Court Cooperative housing (1913) at Spruce Street and Sumach Street is an outstanding Canadian example of Garden City planning, derived from Arts and Crafts principles. Because the Movement claimed to be “styleless”, like Queen Anne, its architecture cannot be readily classified by specific motifs. Some Cabbagetown examples have been partly influenced by regional variations.

Many Cabbagetown houses built in the 1920s have distinctly Southern Ontario characteristics. Most prevalent in Cabbagetown is the largely unornamented “Tuscan” variation in which gabled semi-detached and detached houses are fronted by porches supported on Tuscan columns or half columns. A similar type occurs in several nongabled versions, in which a bay is applied above the porch, often aligned with a roof dormer. Several of theses houses occupy the old Toronto General Hospital.

Inspired by the “honesty” of Medieval building, and theorized by Ruskin and William Morris in the late nineteenth century, the Arts and Crafts Movement advocated traditional materials and building practices, good craftsmanship and simple ornamentation.

In Toronto, the leading Arts and Crafts exponent was the architect Eden Smith. His design for what is now the Spruce Court Cooperative housing (1913) at Spruce Street and Sumach Street is an outstanding Canadian example of Garden City planning, derived from Arts and Crafts principles. Because the Movement claimed to be “styleless”, like Queen Anne, its architecture cannot be readily classified by specific motifs. Some Cabbagetown examples have been partly influenced by regional variations.

Many Cabbagetown houses built in the 1920s have distinctly Southern Ontario characteristics. Most prevalent in Cabbagetown is the largely unornamented “Tuscan” variation in which gabled semi-detached and detached houses are fronted by porches supported on Tuscan columns or half columns. A similar type occurs in several nongabled versions, in which a bay is applied above the porch, often aligned with a roof dormer. Several of theses houses occupy the old Toronto General Hospital.

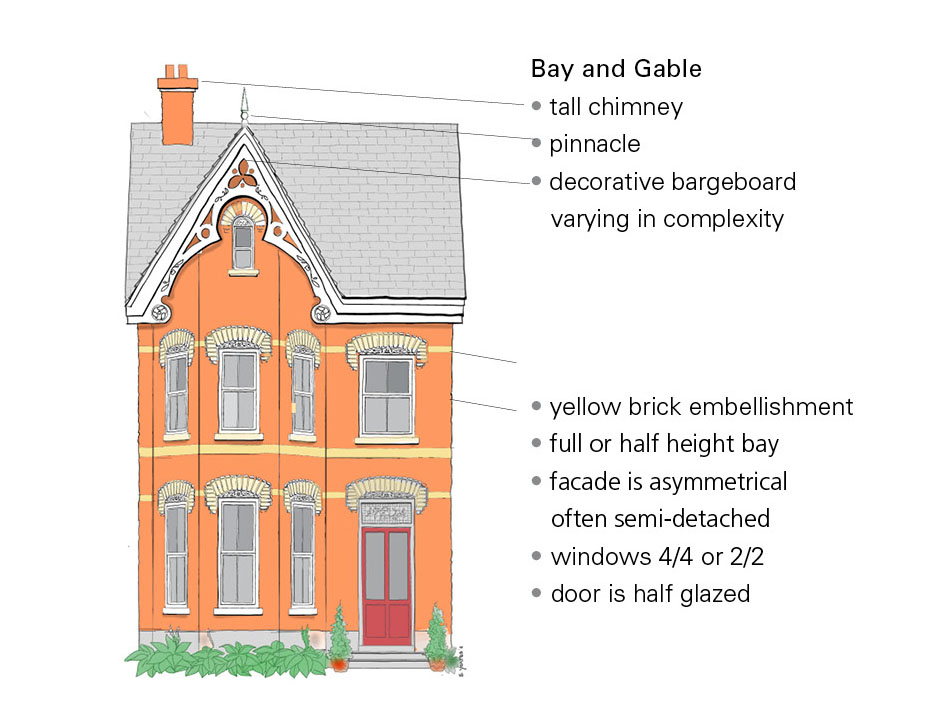

Probably the most prevalent Cabbagetown style, most were built in the later 1880s during a strong economic and population boom. Practically every Cabbagetown street has its share of elegant Bay & Gables.

Note:

- Strong vertical emphasis in which the lines of the bay, together with the narrow openings, draw the eye to the crowning gable and its vigorous display of carved gable board and supporting brackets.

- Unique to Southern Ontario is its combination of varied gable ornamentation, red and yellow brick and two or four light sash windows.

- Half-glazed panelled and transomed entrance doors.

- Variations: half Bay & Gable where the bay fronts only the ground floor often capped by an open fretwork dwarf parapet, and/or by a quasi-mansard roof in tin or copper.

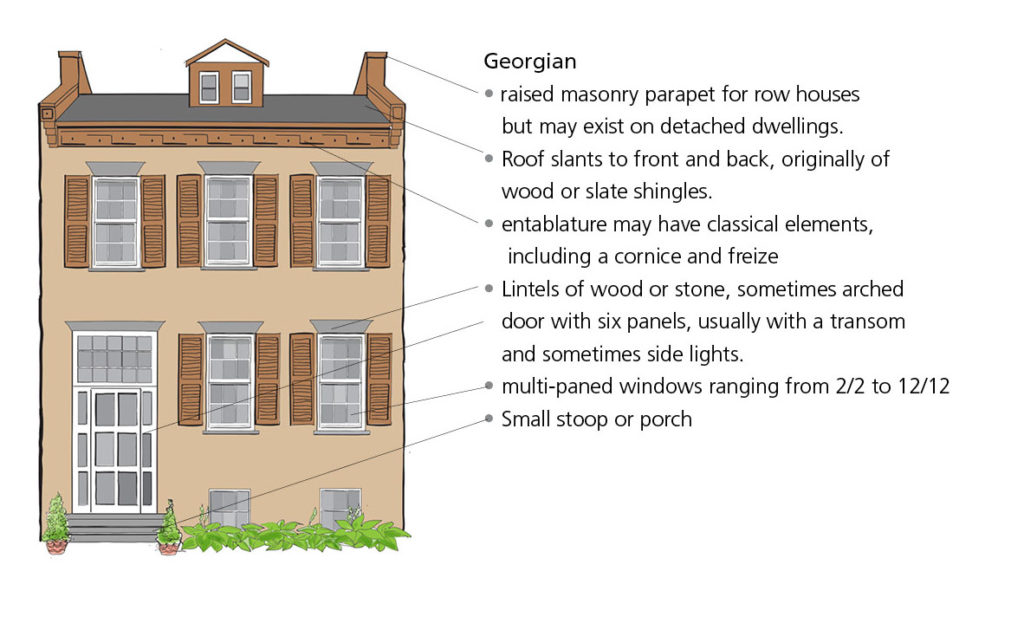

The earliest of Cabbagetown styles, these mostly brick-clad houses were built in our neighbourhood between 1840 and 1870. Elegant and austere, the Georgian house has a sparsely ornamented, symmetrical façade.

Note:

- Sometimes windows are four-light sashes but more often 8-12 lights.

- The entrance door is usually centrally located, half-glazed, panelled, with sidelights.

- There often is a semi-circular sunburst transom above the door.

While the Bay-n-Gable style, in its strong verticality, might be regarded as Gothic in inspiration, particularly when accompanied by pointed arch openings, as on Amelia Street, Cabbagetown has several fine examples from the same period of pure Gothic Revival houses. The style was inspired by the late Romantic Movement, in which a picturesque composition is characterized by high ornamentation.

Note:

- The gables are usually highly ornamented (often with trefoil or quatrefoil carvings).

- There is whimsical detailing. The top window arches are pointed.

This most elaborate and eccentric of all Victorian styles is also the most difficult to define and has many variations. In the 1880s and 1890s it was popular throughout North America for large, expensive residences as varied as the “painted ladies” of San Francisco and the brownstones of Brooklyn. Here, the style is common in The Annex and Rosedale.

Note:

- There are a lot of elaborate details, including terracotta ornamentation and patterned masonry.

- High pitched roof turrets are often found.

Most prevalent between the late 1880s, and 1905, the style in its more robust variation, as in Queen’s Park and Old City Hall, was inspired by the work of the American architect Henry Hobson Richardson.

Note:

- The brickwork is fine and narrow-jointed.

- Terracotta egg-and-dart decorations are often found.

- There is a rugged stone base, often derived from Credit Valley sandstone.

Imported from France, developed in Louis-Napoleon’s Second Empire after 1851; used here until the 1880s. Here, it was applied by the wealthy and workers’ alike.

Note:

- The Mansard roof: a dormer top floor whose facade walls slope steeply inwards and are clad in roof tiles (patterned and originally slate).

- The eaves are often supported by ornamented brackets.

- The window and door openings are frequently arched and emphasized by projecting lintels and pilasters.

- The original windows often have a double casement; two and four light sash windows are also common.

In the late 1800’s the most common form of small house in Ontario and much of the US was the “working-man’s cottage”. This loose design was influenced by British and American architects who were trying to reduce the unsanitary and crowded conditions of working class housing. A model cottage was built at the Crystal Palace industrial exhibition in London in 1851, giving momentum to its appearance in construction pattern books and magazines (e.g. Canadian Farmer in1865) that were used all over North America and Britain. Innovations included water, internal sanitation, fresh air, and separate bedrooms for children – although sanitation was treated as an option in many cases.

The style applied to the cottage was influenced by its location. In Ontario, with many immigrants from Britain, the style leaned to gothic, with details such as finials, barge boarding (gingerbread) and window trim carrying the gothic elements. In addition, a good look at any Cabbagetown cottage may show some Second Empire, Georgian or whatever elements that seemed a good idea at the time. No matter what combination resulted, the outcome was usually pleasing. The early developers of the cottage designs were also trying to raise the spiritual lives of what they would consider the scrabbling classes by improving the aesthetics of their experience. These houses were intended to be simple, efficient, economical and beautiful.

Architecture, either practically considered or viewed as an art of taste, is a subject so important and comprehensive in itself, that volumes would be requisite to do it justice. Buildings of every description, from the humble cottage to the lofty temple, are objects of such constant recurrence in every habitable part of the globe, and are so strikingly indicative of the intelligence, character, and taste of the inhabitants, that they possess in themselves a great peculiar interest for the mind.

Andrew Jackson Downing, American Architect (1815-1852)